Tesla's Cybertruck: A Futuristic Design Sabotaged by Hypermasculinity

A few weeks before Tesla’s Cybertruck reveal in November 2019, Elon Musk teased the vehicle’s radical design on Twitter:

“Cybertruck doesn’t look like anything I’ve seen bouncing around the Internet. It’s closer to an armored personnel carrier from the future.”

At the time I rolled my eyes — a “futuristic armored personnel carrier” felt more like marketing hyperbole than reality. But he wasn’t lying! A futuristic armored personnel carrier, indeed.

The amount of creative ambition it must have taken the design team to drag Cybertruck all the way from concept to reality is impressive. I can’t imagine Ford, Chevrolet, or any other manufacturer producing something as polarizing because novelty inherently breeds resistance.

That’s why bringing something fundamentally new into the world is so admirable — it requires both unrelenting vision and grit. You can’t be Picasso without being Picasso.

Actually, now that I mention it, looking at the Cybertruck is similar to taking in a Picasso painting.

Like, hey, that’s not what a truck is supposed to look like.

Regardless of whether I appreciate its look or feel, the Cybertruck has redefined my understanding of what a “truck” is or can be, and for that reason alone it requires my respect.

Defining terms is exactly what UK designer and Yale graduate David Rudnick describes as the role of designers:

If I say a word to you that has a visual connotation — like “chair” — every one of you will have some chair that you picture in your head. That image, or that idea of what a chair is, will be different for all of you because it can only be built out of your own experiences. Maybe it’s the chair in your family’s house, or the one in your bedroom.

That “chair” is the noun, it’s a term. And what I call the “narrative” is the individual’s unique experience of the term.

This is what a designer does every time we put work in front of people: we are making a conscious intervention into their narratives. We are creating a moment in their history of something.

For better or for worse, Tesla designers have succeeded in creating a moment in my history of “truck.” Not by replacing my mental image of a “truck,” but by creating a new category for the term altogether. My definition has been expanded.

In this way, the Cybertruck reveal reminds me of the first iPhone launch. Steve Jobs anticipated that the concept of iPhone would break consumers’ understanding of the term “phone.” So to explain it, Jobs combined terms together. In his keynote presentation he repeated one line over and over again:

“It’s a phone. It’s an iPod. It’s an internet communicator.”

The framework even extended to the software — iOS 1.0’s music app was literally called “iPod.”

Choices like these are how designers make new things feel less intimidating. The familiarity created by referencing the past (even if its subtle) provides a contextual framework for consumers to understand what, exactly, this newfangled thing is.

So what contextual framework is Tesla providing for Cybertruck, the fully armored pickup that can accelerate faster than a Porsche and beat the Ford F-150 in a game of tug of war? On the Cybertruck product page, Tesla deploys Jobs’ strategy to describe the vehicle:

Better utility than a truck with more performance than a sports car.

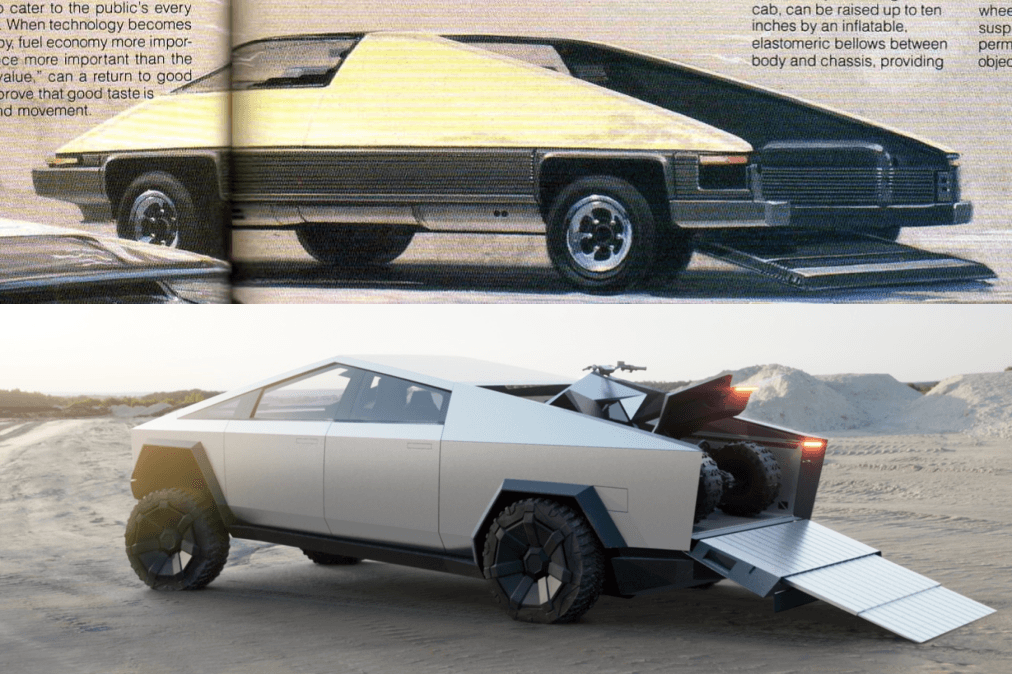

While I doubt it was an actual reference pinned on the wall of Tesla’s design studio, I stumbled upon a Tweet that shows a strikingly similar concept vehicle from 1979 that was published in — wait for it–Penthouse magazine:

Inspiration or not, they share a similar DNA — it’s not an accident that the Cybertruck feels like it was hallucinated into existence by the male gaze. When Reddit user a_blue_ducks described the vehicle as a “massive stainless steel dong,” they meant it as a compliment.

Judging by the two references Elon Musk did cite as the primary inspiration for the Cybertruck design — the Blade Runner film and the car/submarine from the 1977 James Bond film The Spy Who Loved Me — this perception is exactly what Tesla wants consumers to have.

As Elizabeth Bisley, co-curator of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s car design exhibition, explains in her Cybertruck critique:

Both films imagine the future of the car as a highly individualised and powerful technology. Rather than offering an alternative to existing designs, Musk pushes these ideas to newly dehumanised heights.

As a result,

The truck seems the vehicular equivalent of a nuclear bomb shelter — privately-owned and designed for individual survival, in possibly dire conditions, outside of any cogent societal order.

This is the tragedy of Cybertruck: for all its inspirational futuristic qualities, the design is built on the premise of a hyper masculine dystopia. Cybertruck says “get in or die.” But couldn’t the Cybertruck design have been radical and hopeful?

At a TED Talk in 2017, Musk gave insight into his motivations with one of his most famous quotes:

“I’m not trying to be anyone’s savior. I’m just trying to think about the future and not be sad.”

Besides its technological feats, I don’t know what about the Cybertruck is supposed to inspire optimism. Picturing the hundreds of thousands of preordered Cybertrucks on the road feels — as it was designed to — apocalyptic.

If Tesla’s Model S, 3, X, and Y reflect Musk’s desire for a better world here on earth (and teenage boy humor), Cybertruck reflects his core belief that Mars is the only viable long term option.

One month before the Cybertruck event, Volvo announced their surprisingly pragmatic vision for an entirely electric, more sustainable, safer future (the sent of Tesla’s influence was thick). At the event, Volvo debuted their first all-electric XC40:

While these vehicles are targeting two different consumer segments, the framing of the XC40 embraces a future that’s both more hopeful and less patriarchal. From Volvo’s perspective, these ideals seem to be intrinsically linked.

The design of the XC40 will quickly be forgotten in history. It’s sensible, forward thinking, appealing, but not groundbreaking. It didn’t redefine my term for “SUV.” But unlike the “massive stainless steel dong” that is the Cybertruck, the XC40 projects a future worth building towards. In my opinion, that’s far more important than creating something new.

Justin's "Bonsai" Newsletter

A personal newsletter on life, culture, and design.